November 3

Markets and Stocks

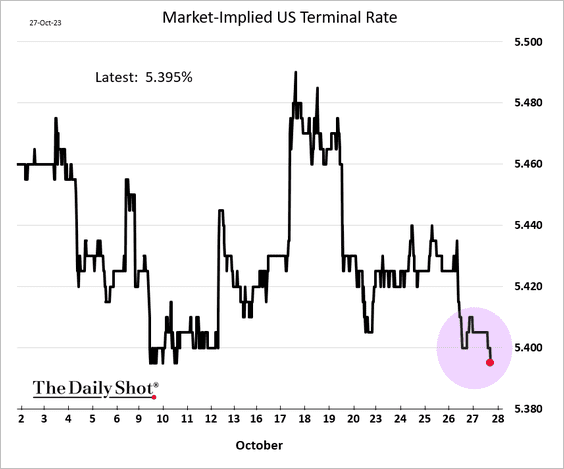

The market believes that the rate hiking cycle is over.

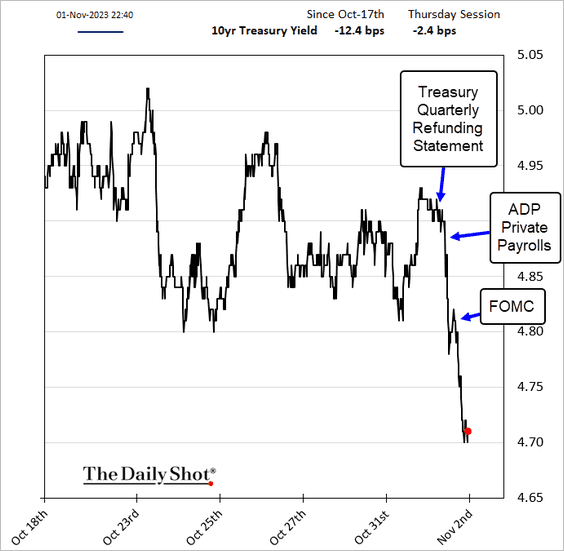

Treasury yields have fallen sharply. As I write, the 10 year is trading with a yield of 4.66%, down 24 basis points from just last week.

My bullish call is premised on the 10 year yield to fall below 4% by Q2 of 2024. I also anticipate modestly rising earnings.

The weekly jobless claims data and the continuing claims information suggest a slowly softening labor market.

The S&P 500 is back above its 200 day moving average.

I expect oil prices to fall toward $75 a barrel, West Texas Intermediate. Russia is ignoring its agreement with Saudi Arabia to cut exports. And the economy in Saudi Arabia is contracting because oil exports are down. See Bloomberg Energy.

Qualcomm sees an upturn in demand for chips for smartphones. I like the semiconductor industry.

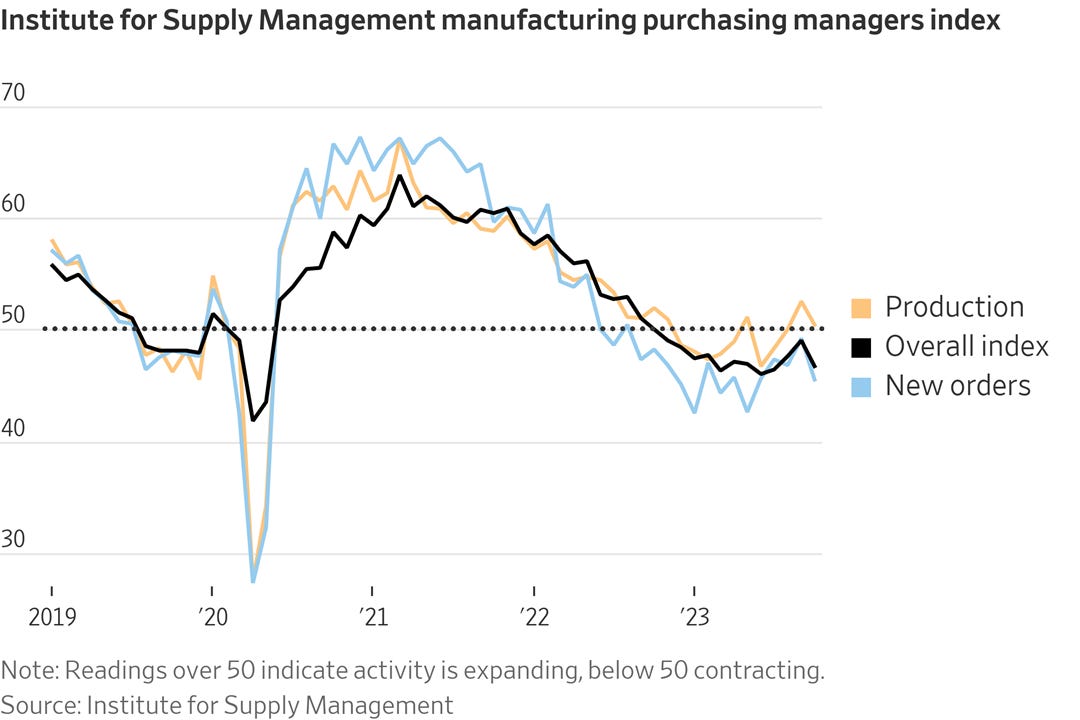

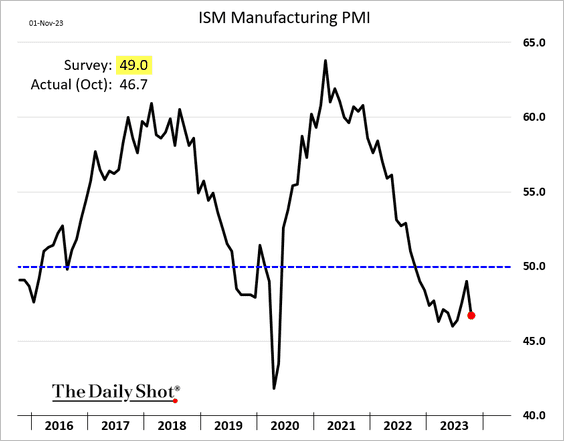

The manufacturing sector is weak. The Journal reports:

A gauge of factory activity fell to its lowest level since July. The Institute for Supply Management's purchasing managers index dropped to 46.7 in October from 49 in September. A reading below 50 indicates activity is contracting. "Amid a complacency around recession warning alarms, the ISM manufacturing index is flashing red.”

Economics

The corporate tax cuts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act are paying for themselves. In many ways, cutting corporate taxes has a flywheel effect on investment, wages and overall economic growth.

Unfortunately, corporate taxes will increase sometime soon. The typical voter does not understand corporate tax policy. And the typical voter doesn’t care who pays more, as long as he or she is not left holding the tax bag.

But the typical voter will cry when long term economic growth is lower and his or her compensation grows only slowly.

Members of Congress are cynics. They care about being re elected and little else.

The below referenced NBER working paper which I highlighted a few days ago was disseminated during the week of October 22. The New York Times is silent on the matter.

The Journal says: Economists from Harvard, Princeton, the University of Chicago and the U.S. Treasury report in a new National Bureau of Economic Research paper on “the investment and firm valuation effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, the largest corporate tax reduction in the history of the United States.”

The authors share a number of findings:

First, the TCJA caused domestic investment of firms with the mean tax change to increase by roughly 20% relative to firms experiencing no tax change. Second, the TCJA created large incentives for some U.S. multinationals to increase foreign capital, which rose substantially following the law change. Third, domestic investment also increases in response to foreign incentives, indicating complementarity between domestic and foreign capital in production. Fourth, the general equilibrium long-run effects of the TCJA on the domestic and total capital of U.S. firms are around 6% and 9%, respectively. Finally, in our model, the dynamic labor and corporate tax revenue feedback in the first 10 years is less than 2% of baseline corporate revenue, as investment growth causes both higher labor tax revenues from wage growth and offsetting corporate revenue declines from more depreciation deductions.

The results of the Trump corporate tax reform were more business investment, more growth, more wages for workers—and little impact on government revenue as lower corporate tax rates were offset by an expanding economy. Game, set, match.

Responding to the study, William McBride and Alex Durante of the Tax Foundation elaborate on how lower corporate tax rates still generate voluminous receipts for the Treasury, even within the 10-year windows of Beltway budgeting:

Regarding the TCJA’s impact on tax revenue, the study finds small dynamic effects within the 10-year budget window after accounting for increased economic activity. Tax revenues from labor increase due to the increased wage growth but are offset by a decline in corporate tax revenue particularly from bonus depreciation in the first few years after enactment. However, by year 10, dynamic corporate tax revenue gains begin to offset static corporate tax revenue losses while dynamic labor tax revenue reaches about 15 percent of baseline corporate tax revenue. This is sufficient to fully offset the static revenue losses from the corporate provisions by the end of the budget window.

The new study has economists buzzing on the platform formerly known as Twitter. “These are the most convincing estimates of the response of investment to corporate tax rates that I’ve ever seen,” says Harvard’s Jason Furman, former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers during the Obama administration. He is not among the study authors but describes the findings in a series of posts on X:

Taxes actually do matter... Companies that saw larger reductions in tax rates from the TCJA also experienced larger increases in investment in the years that followed...

Note they find that they increase investment overseas and that this investment is a complement that leads them to increase investment in the United States.

Importantly, Jason Furman, now a senior at Harvard, was former President Obama’s senior economics adviser.

And the Journal points to Ireland for another example of how low corporate taxes pay for themselves.

European Union officials and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen are pushing for a global minimum corporate tax, and no wonder. High-tax countries are getting bled to death, while low-tax ones experience stunning growth.

Ireland, whose economy grew by 12.5% last year—faster than any other European nation—is one of the greatest tax-cutting success stories of modern times. The Journal recently reported that Ireland is “swimming in money.” It’s a vivid example of the Laffer Curve, which shows that lower tax rates can result in faster growth and higher revenue.

In the 1990s, Ireland had a dismal welfare-state economy. Between 1971 and 1991, its national debt as a share of gross domestic product rose from 40% to 95%, and its unemployment rate topped out just shy of 18% in 1987. But in 1995, Dublin implemented a controversial about-face economic plan. The country replaced its 40% corporate tax rate with a 12.5% rate, phased in over about a decade. Ireland became a magnet for new business and capital investment.

It worked. Even the most optimistic architects of this low flat rate couldn’t have imagined the economic recovery it would launch. The American Chamber of Commerce Ireland reports that the number of U.S. multinational companies operating in Ireland now stands at about 950, with 209,000 employees. Only five million people live in Ireland. This is the equivalent of a U.S. policy creating 10 million jobs.

Ireland is an industrialized country with one of the world’s largest budget surpluses, thanks to new tax revenue, especially from big tech and pharmaceutical companies domiciled in Dublin. The mystery is why other nations haven’t imitated the Irish. The left has ridiculed international tax competition as a “race to the bottom,” even as Ireland has raced straight to the top.

The Biden administration—which has proposed raising the U.S. corporate tax rate from 21% to between 25% and 30%, as well as higher tax rates on capital gains and dividends—doesn’t get this at all. These are self-defeating policies that the Irish rejected, to their great benefit.