July 4

Good news - the June employment report was stronger than expected.

The United States economy is exceptional in spite of politicians.

What is good for the private sector is good for America.

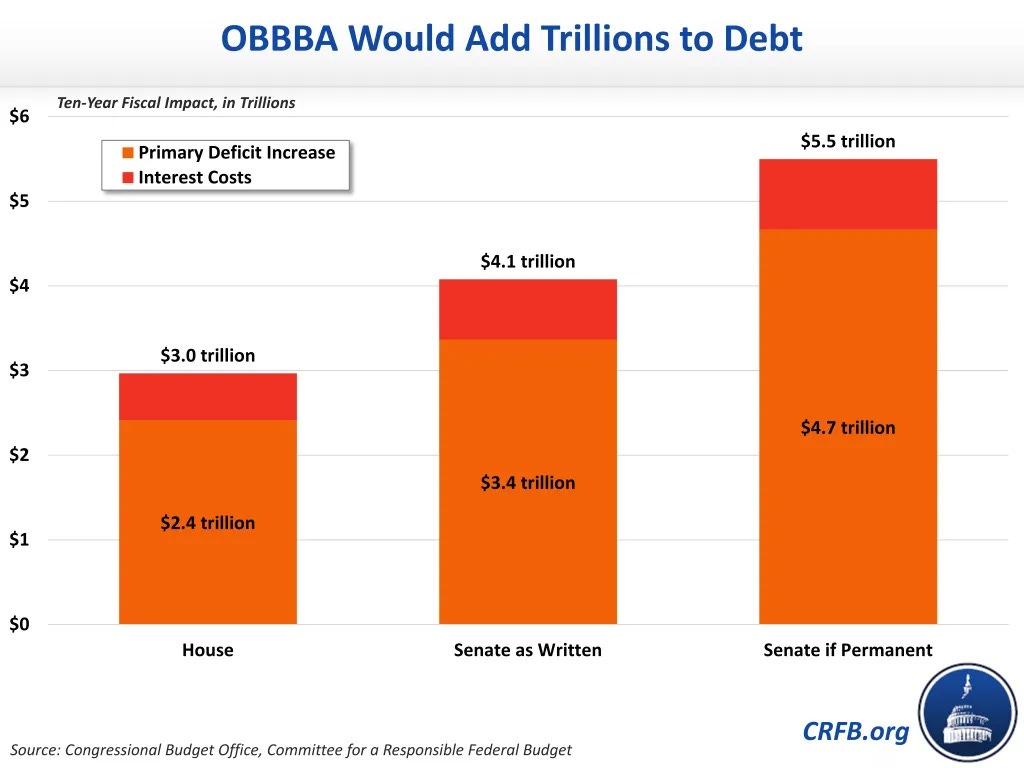

The big beautiful bill, i.e. the reconciliation bill, will add trillions to the deficit.

It is more fiscally irresponsible than Biden’s spending legislation.

Trade thaw? The U.S. government has rescinded its export restrictions on chip-design software to China. See CNBC.

The border is secure.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/02/us/politics/border-crossings-trump.html

Bitcoin and other crypto “assets” are big business for institutions.

At BlackRock, the world’s biggest asset manager, a Bitcoin exchange-traded fund now generates more revenue than its signature tracker of the S&P 500 Index. The $75 billion ETF has seen a torrent of cash from institutional and retail investors.

Markets and Stocks

New all time highs are bullish. See Nick Glydon at Rothschild. But stocks are not cheap, invest don’t trade. I am focusing on the AI stack, the largest financial institutions, including AXP, the defense sector, natural gas and nuclear power to generate electricity for data centers as well as selected other names like Boeing, Disney, Lilly, CAT and ETN.

In big technology, I want to highlight Nvidia, Meta and Alphabet.

ASML is a fantastic long term investment.

The June employment report shows a reasonably strong and very resilient labor market. The jobs number was 147,000. The market expected a number around 90,000. And wage growth continues to moderate. Hourly wages were up 0.2%. The key takeaways, no recession and continued progress on inflation.

Jobless claims fell to the lowest level in 6 weeks.

Economics

On the Reconciliation bill, taxes should be raised on everyone. Entitlements must be reformed. Raise the retirement age. Raise Social Security and Medicare taxes on people not employers. Raise Medicare and Medicaid co pays. Continue to chip away at the welfare state, particularly SNAP, food stamps. I will be snarky. I have NEVER seen an American who is not an addict or deranged who is not getting enough to eat. Real poverty has been effectively eradicated. See Mayer and Sullivan.

Making permanent the R&D deduction, 100% immediate depreciation and expanding the effective use of debt are great policies. The most economically efficient tax rate on business is ZERO.

Tyler Cowen discusses the BBB BS bill.

So far I am not finding them very impressive.

To be clear, there are many things — big things — I do not like about the bill. I would sooner cut Medicare than Medicaid (that said, I do not find the idea of cutting health care spending outrageous per se). The corporate rate ends up being too low, given the budget situation. No taxes on tips and overtime is crazy and cannot last, given the potential to game the system, plus those are not efficient tax changes.

I strongly suspect that if I knew more of the bill’s details (e.g., what exactly is the treatment of nuclear power in the current version?), I would have more complaints yet. I do not wish to boost taxes on solar power. Veronique de Rugy criticizes the underlying CEA projections.

That all said, doing the budget is not easy, especially these days. Maybe I have read fifteen or so critiques of BBB, and have not yet seen one that outlines which spending cuts we should do. Yet comparative analysis is the essence of economics, or indeed of policy work more generally. In that sense they have yet produced critiques at all, just complaints. Alternatively, the critics could outline all the tax hikes that would put the budget on a sustainable path, but I do not them doing that either. Again, no comparative analysis.

If you don’t want to cut health care spending, what do you want to cut? I am willing to cut health care spending, preferring to start with richer and older people to the extent that is possible.

You can always spend more on health care and save more lives and prevent some suffering. But what is the limiting principle here? Simply getting angry about the fact that lower health care spending will have some bad outcomes is more a sign of a weak argument than a strong argument. Again, a strong argument needs comparative analysis and some recognition of what is the limiting principle on health care spending. I am not seeing that. I am seeing anger over lower health care spending, but no endorsements of higher health care spending. I guess we are supposed to be doing it just right, at least in terms of the level?

It is commonly noted that the depreciation provisions and corporate cuts will increase the deficit, but how many of the critics are noting they are also likely to increase gdp (but by enough to prove sustainable?)? I write this as someone who thinks the proposed Trump corporate tax rate is too low, but I am willing to recognize the trade-offs here.

Another major point concerns AI advances. A lot of the bill’s critics, which includes both Elon and many of the Democratic critics, think AI is going to be pretty powerful fairly soon. That in turn will increase output, and most likely government revenue. Somehow they completely forget about this point when complaining about the pending increase in debt and deficits. That is just wrong.

It is fine to make a sober assessment of the risk trade-offs here, and I would say that AI does make me somewhat less nervous about future debt and deficits, though I do not think we should assume it will just bail us out automatically. We might also overregulate AI. But at the margin, the prospect of AI should make us more optimistic about what debt levels can be sustained. No one is mentioning that.

It also would not hurt if critics could discuss why real and nominal interest rates still seem to be at pretty normal historical levels, albeit well above those of the ZIRP period.

Overall I am disappointed by the quality of these criticisms, even while I agree with many of their specific points.

How the 1942 Japanese Exclusion Impacted U.S. Agriculture

In 1942 the United States forcibly interred Japanese Americans in camps far away from where they were living when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December, 1941. Many of the Americans who were removed had been skilled agricultural workers. NBER working paper 33971 explains that some California agricultural counties suffered permanent damage from the internment policy.

Today, Trump’s policy of expelling agricultural workers who are illegal immigrants will probably have lasting negative consequences for certain economic sectors and geographies of the country.

Trump’s policy seems to be “let’s hit ourselves in the head over and over and see what happens.”

In the early 1940s, Japanese American farmers represented a highly skilled segment of the agricultural workforce in the Western United States, characterized by higher education levels and more specialized farming expertise than U.S.-born farmers.

During World War II, around 110,000 Japanese Americans (and 22,000 agricultural workers among them) were forcibly relocated from an “exclusion zone” along the West Coast to internment camps.

Most never returned to farming. Using county-level panel data from historical agricultural censuses and a triple-difference (DDD) estimation approach we find that, by 1960, counties in the exclusion zone experienced 12% lower cumulative growth in assessed farm value for each percentage point reduction of their 1940 share of Japanese farm workers, relative to counties outside the exclusion zone.

These counties also lagged in farm revenues, adoption of high-value crops, mechanization, and adoption of commercial fertilizer. We present suggestive evidence of broader negative spillovers to local economic growth beyond the agricultural sector.

Taken together, our findings highlight the long-run economic costs of this policy, illustrating how the loss of skilled farmers can reduce agricultural growth and, in a time of fast technological adoption, may have negative effects on the whole regional development.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w33971

Politics

The European Union regulates. The United States innovates.

Exclusive: Top European chief executives have urged the EU to halt its landmark artificial intelligence act, as the bloc considers watering down key elements of the law due to come into force in August. The heads of 44 major companies, including Airbus and BNP Paribas, warned in a letter that it would threaten the region’s competitiveness. See FT.

The United States needs more data centers and more energy today, not tomorrow.

OpenAI has agreed to pay $30bn a year to lease computing power from Oracle, in one of the largest cloud agreements to date for AI. The deal, which marks a big expansion of OpenAI’s “Stargate” AI infrastructure project, would lease 4.5 gigawatts — about a quarter of the US’s current operational data centre capacity. See FT.

Great Britain

Thomas Rogan explains that the United Kingdom is in permanent economic decline because politicians in the country refuse to dismantle the welfare state.

On the weakening U.K. government's complete failure to address fiscal realities.

India

Alex Tabarrock explains that India must reform its government jobs sector.

In India, government jobs pay far more than equivalent jobs in the private sector–so much so that the entire labor market and educational system have become grossly distorted by rent seeking to obtain these jobs. Teachers in the public sector, for example, are paid at least five times more than in the private sector. It’s not just the salary. When accounting for lifetime tenure, generous perks, and potentially remunerative possibilities for corruption, a government job’s total value can be up to 10 times that of an equivalent private sector job. (See also here).

As a result, it’s not uncommon for thousands of people to apply for every government job–a ratio far higher than in the private sector. In one famous example, 2.3 million people submitted applications for 368 “office boy” positions in Uttar Pradesh.

The consequences of this intense competition for government jobs are severe. First, as Karthik Muralildharan argues, the Indian government can’t afford to pay for all the workers it needs. India has all the laws of say the United States but about 1/5 th the number of government workers per capita leading to low state capacity. But there is a second problem which may be even more serious. Competition to obtain government jobs wastes tremendous amounts of resources and distorts the labor and educational market.

If jobs were allocated randomly, applications would be like lottery tickets with few social costs. Government jobs, however, are often allocated by exam performance. Thus, obtaining a government job requires an “investment” in exam preparation. Many young people spend years out of the workforce studying for exams that, for nearly all of them, will yield nothing. In Tamil Nadu alone, between one to two million people apply annually for government jobs, but far less than 1% are hired. Despite the long odds, the rewards are so large that applicants leave the workforce to compete. Kunal Mangal estimates that around 80% of the unemployed in Tamil Nadu are studying for government exams.

Classical rent-seeking logic predicts full dissipation: if a prize is worth a certain amount, rational individuals will collectively spend resources up to that amount attempting to win it. When the prize is a government job, the ‘spending’ is not cash, but years of a young person’s productive life. Mangal calculates that the total opportunity cost (time out of the workforce) that job applicants “spend” in Tamil Nadu is worth more than the combined lifetime salaries of the available jobs (recall jobs are worth more than salaries so this is consistent with theory). Simply put, for every ₹100 the government spends on salaries, Indian society burns ₹168 in a collective effort of rent-seeking just to decide who gets them. The winners are happy but the loss to Indian society of unemployed young, educated workers who do nothing but study for government exams is in the billions. Indeed, India spends about 3.86% of GDP on state salaries(27% of state revenues times 14.3% of GDP). If we take Mangal’s numbers from Tamil Nadu, a conservative (multiplier of 1 instead of 1.68) back of the envelope number suggests that India could be wasting on the order of 1.4% of GDP annually on rent seeking. (Multiply 3.86% of GDP by 15 (30 years at 5% discount) to get lifetime value and take .025 as annual worker turnover.) Take this with a grain of salt but regardless the number is large.

India’s most educated young people—precisely those it needs in the workforce—are devoting years of their life cramming for government exams instead of working productively. These exams cultivate no real-world skills; they are pure sorting mechanisms, not tools of human capital development. But beyond the staggering economic waste, there is a deeper, more corrosive human cost. As Rajagopalan and I have argued, India suffers from premature imitation: In this case, India is producing Western-educated youth without the economic structure to employ them. In one survey, 88% of grade 12 students preferred a government job to a private sector job. But these jobs do not and cannot exist. The result is disillusioned cohorts trained to expect a middle-class, white-collar lifestyle, convinced that only a government job can deliver it. India is thus creating large numbers of educated young people who are inevitably disillusioned–that is not a sustainable equilibrium.

Mangal valiantly proposes redesigning the exams to reduce waste, but this skirts the core issue: India’s wildly skewed public wage structure. Government salaries far exceed what is justified by GDP per capita or job requirements, distorting education, employment, and unemployment throughout the entire economy in deeply wasteful ways. The only real solution is to bring public sector pay back in line with economic fundamentals.